Top Ten Problems with Digital Radio

On July 6, Prometheus filed comments with the FCC to oppose a proposed power increase for digital radio signals (aka "HD radio"). But since most people haven't heard enough about digital radio to even weigh in on the issue, this month we've put together our Top Ten Problems with Digital Radio.

1. If you don't already own a radio station, HD Radio isn’t for you.

What if only newspaper owners could run Internet blogs? In its current form, HD radio is available only to the tiny world of incumbent broadcasters. That's because HD Radio uses a technology called IBOC--In Band, On Channel. If you already have a radio channel, then you can add a digital signal on either side (called sideband channels). If you aren't part of the club, this technology's not for you.

Each station can squeeze in several new digital channels, because digital takes up less bandwidth than analog. But with no risk of competition from new entrants, HD radio isn't likely to have programming that’s all that much more diverse than what you already hear. Going digital is how the radio industry hopes to catch up with the Internet age, but unlike the Internet, HD Radio (as it’s currently conceived) doesn’t open media access to new voices.

2. It doesn't actually work yet.

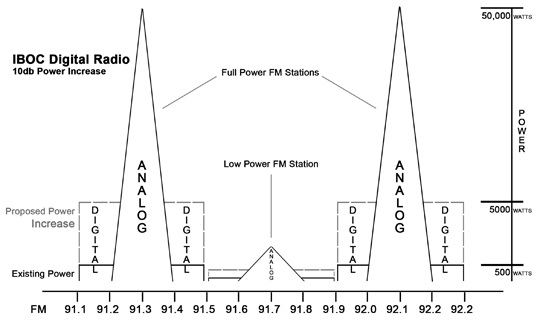

Since 2002, stations have been allowed to broadcast digitally using 1% of the power of their existing analog channel. So a 50,000 watt station can have two 250 watt digital sideband channels (250+250= 500, or 1% of 50,000). Proponents claimed that HD Radio would revolutionize the airwaves with crystal clear reception. It hasn’t worked out that way. In fact, an NPR study showed that digital coverage is worse than analog! The coverage is somewhat worse than analog for mobile listeners (in cars or on portable radios), and way worse for listeners indoors.

3. To make it work, digital broadcasters want to drown out everyone else.

Since HD Radio doesn’t actually work at 1% (see reason #2, above), an alliance of big broadcasters and manufacturers have asked the FCC to raise the power of digital channels to 10%, a idea so risky that even some of the biggest investors in HD are complaining. NPR, whose member stations have invested millions in going digital, has asked the FCC to delay the power increase until more studies are done. Already, the NPR study has shown that a 10% increase would cause significant interference to other stations. In fact, many analog stations could lose one-third or more of their covered population. Even scarier (if you’re NPR, anyway), IBOC can create self-interference, so a digital radio signal could drown out its own analog parent channel (you know, the one people actually listen to).

4. Low power community radio risks losing the most.

Since Low Power FM stations (LPFMs) have a much smaller signal strength than other radio stations, it’s easier to drown them out. If HD Radio ever takes off, this could become a serious problem for LPFM.

The irony is that the same industry broadcasters who claim LPFMs will cause interference are claiming that HD Radio, already more powerful than LPFM, is no problem. With the proposed power increase to 10%, each sideband of a 50,000 watt station would broadcast at 2,500 watts, way beyond the LPFM maximum of 100 watts. The difference is that LPFMs represent new voices in our media, and IBOC stations are owned by industry insiders.

And while overzealous interference protections limit the LPFM service, IBOC technology doesn’t yet have any special rules in place to protect LPFMs or other stations from new kinds of interference. In fact, the interference that IBOC could cause LPFMs has yet to even be studied.

5. Tons more stations, but no new public interest obligations.

With the advent of digital technology, there’s room for many new stations on the dial (though all owned by the same broadcasters as the old stations, thanks to IBOC). How do these stations compensate the public for this lucrative new use of the public airwaves? Since the FCC won’t acknowledge HD radio as a spectrum giveaway, they don’t. Even though HD broadcasters stand to make millions, they do so without any new requirements to serve the public good.

Like most problems with HD Radio, this one could be easily solved. Digital broadcasters could be required to donate a portion of their new revenues to a public interest fund. Or they could be required to share a portion of their new bandwidth with noncommercial, educational groups. Or be obligated to produce eight hours of local programming per day. But for now, the spectrum used by HD Radio is another slice of the public pie served up to the private sector, for free.

6. Anonymous interference.

Unlike regular interference between analog radio stations, interference from an HD station just sounds like white noise, so there’s no way for listeners to identify the problem station. With no way for listeners to complain, the FCC probably won’t ever hear about most HD-caused interference.

7. The future of radio is entrusted to a single company.

Although digital radio could be implemented in various ways (and has been, elsewhere around the world), the FCC decided to go with a proposal from the Ibiquity Corporation for IBOC (in band, on channel broadcasting). Not only is IBOC limited to the in-crowd of industry broadcasters (see reason #1), the whole system is run by this single corporation. Broadcasters must license the technology directly from Ibiquity, paying up to $25,000 just to get started, plus a percentage of their revenues on an ongoing basis. Ibiquity charges licensing fees on every transmitter and every receiver manufactured. It’s a monopoly. And if digital really is the future of radio, that means that someday all radio will be controlled by one company. (And you thought Clear Channel was bad.) Better hope they like your station’s programming!

8. Proprietary software keeps this new technology shackled.

To protect their monopoly on HD Radio and all the future profits that could entail, Ibiquity relies on a closed, proprietary software structure. It’s an outdated business model that prevents others from “checking under the hood” or contributing ideas that might improve digital radio.

9. HD radios are expensive.

Most HD radios cost $150 and up--a lot to pay for a technology that doesn’t work as well as regular analog radio, but is completely controlled by the same old suspects (incumbent broadcasters).

10. What kind of future is this, anyway?

Leave it to the broadcasting industry that brings you channel after channel of the same garbage to propose a digital future with no new ideas. We have new channels but no new voices. New software that’s closed to outside innovation. A spectrum grab with no new service to the public. And a single company holding the reins. It’s not the kind of media future that most of us envision.

Given all of these problems, it’s hard to understand why HD Radio is still on the table. The best thing the FCC could do is go back to the drawing board. When first introduced, IBOC (In-band, On-channel) was an attractive idea because it offered digital radio without eliminating analog channels (making analog receivers obsolete). Now that new spectrum has been made available by vacated analog television channels, there are other ways for radio to join the digital age, leaving plenty of room for everyone without causing interference to analog stations.

But since the FCC isn't considering alternatives, the least they could is institute public interest obligations, require broadcasters to share their new bandwidth, and make sure that IBOC doesn't interfere with analog stations (including LPFM). Prometheus has a Petition for Reconsideration on record to demand that IBOC's spectrum giveaway come with new public interest obligations. Our most recent comments, filed July 6, 2009, repeat this call, and ask that the FCC consider the results of a forthcoming NPR interference study before granting a power increase. Stay tuned for updates this as we continue to demystify HD radio and fight for a brighter digital future!